Links and local information for Malham, North Yorkshire UK

Art, Literature, TV & Film

Nothing commends Malhamdale so much as a rite of passage which is almost a given for generations of schoolchildren: obliged, often against their better instinct, to spend the day in Malham’s hinterland by geography teachers from across the region, teeming classes can be seen daily decanting from coaches, or wandering the paths to sites of ‘geological excellence’ – the Cove and Gordale Scar.

And if interest in clints, grikes and dry valleys is sometimes lost in the unbridled zeal of being let, albeit briefly, off the academic hook, some of that magic dust will nevertheless rub off, bringing many of the kids back to this unique place of homage, into adulthood and beyond.

Not least to the places that rang most meaningful to them on their first visit, the places that make up the architectonic backdrop of television and film dramas, the dramatic landscapes of mythmaking, of science fiction and of fantasy whose appearance is richly suggestive of a darkly concealed past, and infused with a steroidal, imagination-capturing, sense of an alternative reality. And, of course, the celluloid stars who gravitate to this corner of the Dales in tandem with the cavalcades of studio equipment and crew. In 2019, Gordale Scar played host to an ‘encampment’ of Netflix production teams for the filming of an episode of the worldwide fantasy hit, The Witcher, but of greater significance to the star-spotters and salivators amongst onlookers, was the presence of Henry Cavill (Superman, Geralt of Rivia), and Freya Allan (Princess Cirilla). From fantasy to a version of reality, Gordale has, in recent years, also doubled as the Crimea for the ongoing television series Victoria.

Cavill is only the most recent of many superstars to grace the amphitheatrical ‘stage’ at Malhamdale’s head, for the inherent drama of the landscape is a gift to filmmakers, writers and artists. Daniel Radcliffe’s appearance on the limestone pavement atop the Cove for a sequence in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows is a testament to the surreal quality of the terrain, especially in certain lights. So too, Janet’s Foss and its dense surrounding woodlands and dripping mosses, which was used in the 2017 film, Dark River with Ruth Wilson and Sean Bean. The dramatic aerial perspectives and wooded gulleys of the area appeared at length in the 1989 science-fiction outing, Slipstream, featuring Star Wars’ Mark Hamill, and it is somehow no surprise to learn that several location sequences of the comedy classic, Monty Python’s Holy Grail, were filmed here.

Harry & Hermione on the Limestone Pavement above Malham Cove

Harry & Hermione on the Limestone Pavement above Malham Cove

Complete with its own micro-climate and clouds that glower menacingly over the high edges of vision, Malhamdale is steeped in atmosphere. Allowing for the small dislocation of a geographical fault-line, and the sleight-of-hand replacement of wild gritstone moors with the softer limestone pastels of the Dales, the 1992 take on Wuthering Heights with Juliette Binoche and Ralph Fiennes brooded to extraordinary effect, in no small measure owing to the sheer diversity of perspective.

Nor is the aesthetic draw of the landscape a recent phenomenon for filmmakers: the 1951 melodrama, Another Man’s Poison, was filmed at Bell Busk, Newfield and Malham, and featured American screen goddess, Bette Davis, in a rare British excursion. Preceded two years earlier by A Boy, A Girl and a Bike, whose wide-angles shots utilized the valley’s panoramas liberally, the film gave an early outing to a young Diana Dors and Honor Blackman.

Malhamdale’s popularity with daytrippers and holiday-makers has been enhanced hugely by its wide exposure on mainstream television. In recent years, film crews have become a regular fixture as the demand for programmes on food, cooking, walking and outdoor pursuits has increased exponentially in line with the ascendancy of home-grown produce, and increasing accessibility. The list of documentaries is a continuing phenomenon: from chef Tom Kerridge’s artisan food producers of Top of the Shop, to Adrian Edmondson’s popular Dales series, to Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon’s offbeat gourmandizing in The Trip, to Julia Bradbury’s Best Walks with a View, each has helped to add a seductive dimension of interest to a valley that already excels in natural beauty.

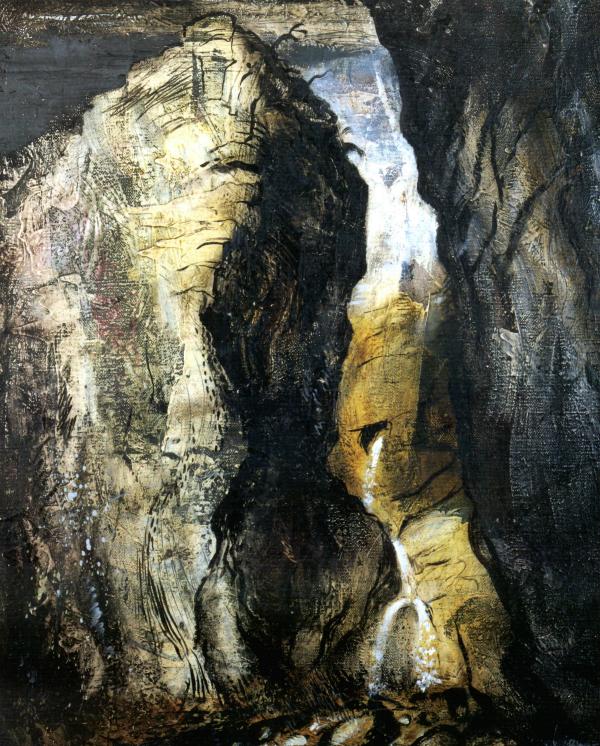

It’s easy to forget that the sense of wonderment we take from being amongst titanic, and titanically beautiful, landscapes is derived from those exponents of a Romantic tradition of thought and reflection who utterly re-shaped our perception in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Taking as their cue the notion of the Romantic Sublime, writers and poets such as Coleridge, Wordsworth, Gray and Ruskin, and artists such as J.M.W. Turner, John Martin and James Ward saw in Malhamdale’s grandiose cliffs, chasms and cataracts, visions of Heaven, or possibly Hell. Ward, in particular, is celebrated as a key painter of the English Romantic tradition. His fittingly huge canvas Gordale Scar (1812-14), measuring an astonishing 3.2mt x 4.2mt, which was displayed at the Royal Academy in 1815, is now resident at the Tate.

James Ward A View of Gordale, in the Manor of East Malham in Craven

The valley has long been a magnet for artists who have found a natural antecedence in the work of their forbears. The present Dale is home to several nationally-renowned artists, whose work is sometimes a mirror to the earlier luminaries: a descendant of three generations of artists, Katharine Holmes’ resonant local landscapes are, in the best sense, Turneresque, whilst David Cook’s Impressionism and attention to detail is counterpointed by his wife, Heather’s, rectilinear shapes and symmetries, and Airton-based artist, Beverley Cook’s, seductive abstractions.

The poet Thomas Gray, on a brief visit in 1769, was struck almost dumb by the spectacular limestone architecture of the valley and could barely articulate a response ‘without shuddering’. Overawed, he could not linger for more than fifteen minutes, amongst what a later poet described as the ‘groynings’ of the landscape. Small wonder that Wordsworth was moved to capturing in verse what he saw on a visit several decades after Gray’s own:

GORDALE William Wordsworth (1819)

At early dawn, or rather when the air

Glimmers with fading light and shadowy eve

Is busiest to confer and to bereave;

Then, pensive votary! let thy feet repair

To Gordale chasm, terrific as the lair

Where the young lions couch; for so, by leave

Of the propitious hour, thou mayst perceive

The local deity, with oozy hair

And mineral crown, beside his jagged urn

Recumbent: him thou mayst behold, who hides

His lineaments by day, yet there presides,

Teaching the docile waters how to turn,

Or, if need be, impediment to spurn,

And force their passage to the salt-sea tides!

Wordsworth’s sonnet imagines a ‘local’ god in the brazen, majestic stonework of the chasm, presiding over its majesty, directing water to its tributary destination, and it is clear that he is caught in a maelstrom of contemplation by the scale of his vision, no less than Ward was in oils.

Subsequent nineteenth century writers were similarly transfixed by the lay of the land, and its potential for suggestion. The hugely wealthy philanthropist, Walter Morrison, who used Malham Tarn House as a summer home for very many years straddling the Victorian period and the early twentieth century, hosted many guests during his tenure, not least some of the leading scientists, thinkers and writers of the time. John Ruskin and Charles Darwin both visited, but more significant, given the immense popularity of his later book, was Charles Kingsley. After a visit in 1858, during which he wrote in fascination at what he saw, it now seems highly likely that some of the earlier chapters of his masterwork, Water Babies, was set in and around the area of the Tarn.*

On the nether side of the class divide in Morrison’s time, was one Betty Chester (nee Banks) who lived at Windy Pike, high above Kirkby Malham. An uneducated farm worker who learned the rubric of poetry by dint of hard graft and self-discipline, her single extant contribution to the world of literature is an homage to the valley in which she lived:

A Poem about Malhamdale

O how I love thee, dear old Malhamdale!

With thy sequestered nooks and lovely vale,

Adorned by curious rocks and shady dells,

Fine waterfalls and rugged, high-peaked fells,

That lavishly display in many a part

The richest beauty of nature’s art

In thee, old Malhamdale.

Thou dost at every season of the year,

In sunshine bright, and wintry storms severe,

Present to my admiring eyes a face

That’s unsurpassed in beauty and in grace.

For, though I wander other sights to see,

Yet find I none that can compare with thee,

Romantic Malhamdale.

For, in the joyous and reviving spring,

What dale is there that can surpass thee in

The charms which budding tree and freshening field

And springing flower in rich abundance yield?

As nature fair arouses out of sleep,

And with consummate skill makes thee complete

In beauty, Malhamdale.

And when the soft and genial summer’s air

Brings into bloom thy flowers of beauty rare,

They with thy new-borne stream and rocks unite

In making thee a wonder and delight,

While birds, which sport so joyously at play

Raise happy songs that drive dull care away

From thee, bright Malhamdale.

Or when the cold and searching autumn’s breeze

Blights the fair flowers, and strips the dark green trees

Of all their leaves, which once were bright and gay

But now are left to wither and decay.

Although thou art of such great charm bereft,

I love thee still for there is beauty left

In thee, fair Malhamdale.

I love to see thee clad in garments fair

Which winter brings and spreads o’er thee with care.

As though to shield thy beauties from the cold,

She doth thee in pure white snow enfold,

And render thee more picturesque and grand,

While wonderingly at Windy Pike I stand

To view thee, sweet Malhamdale.

I live to view thee in the daylight clear,

And when the calm grey twilight hours appear,

Or when the moon sheds forth her mellow light

To cheer and grace the shadows of the night.

No matter when or where I gaze on thee,

Nought can I find but rich sublimity

In thee, my native dale.

A paean to the seasons, Betty’s stanzas are filled with the kind of love for place that local folk understand by intuition and instinct. Written in 1881, her poem is a remarkable legacy.

In more recent times, Kirkby Malham became the home, for several years, of acclaimed American travel writer and all-round wit, Bill Bryson, whose first book, Notes From a Small Island became an instant best-seller whilst he was still resident in the valley. Celebrating the ‘Malhamdale Wave’ in print – that uniquely local gesture of raising a finger of greeting to other road-users from behind the steering wheel – Bill’s affection for the area was no doubt cemented in his fondness for the landscape, and especially the stupendous view looking north towards the Cove from the Settle road out of Kirkby:

“I won’t know for sure if Malhamdale is the finest place there is until I have died and seen heaven (assuming they let me at least have a glance), but until that day comes, it will certainly do.”

Few would argue with the sentiment.

*The North Craven Heritage Trust gives a fulsome and persuasive account of the association in its Journal of 2011:

http://www.northcravenheritage.org.uk/NCHTJ2011/2011/kingsley/kingsley.html

For more information on Malhamdale Art: http://www.kirkbymalham.info/KMI/malhamdale/artists.html

We also have our own local talent such as William Shackleton – artist, William (Bill) Wild – blacksmith, artist and carver, David Cook – artist, Judith Bluck – sculptress, Katharine Holmes – artist, Beverley Hicks – artist and many more.

MALHAM COVE William Wordsworth, 1819.

WAS the aim frustrated by force or guile, When giants scooped from out the rocky ground, Tier under tier, this semicirque profound? (Giants–the same who built in Erin’s isle That Causeway with incomparable toil!)– Oh, had this vast theatric structure wound With finished sweep into a perfect round, No mightier work had gained the plausive smile Of all-beholding Phoebus! But, alas, Vain earth! false world! Foundations must be laid In Heaven; for, ‘mid the wreck of IS and WAS, Things incomplete and purposes betrayed Make sadder transits o’er thought’s optic glass Than noblest objects utterly decayed.

John Piper Gordale Scar, Yorkshire, 1943

Want to keep in touch with occasional special events & offers? then please Subscribe to the Malhamdale Newsletter